By Tom and Jerry Caraccioli

Before the beginning of the Civil War, an estimated 1,500 African-American slaves escaped the shackles and chains of indignity and oppression of Southern landowners each year. Many of them crossed into Canada through communities in Upstate and Central New York.

For many, the Underground Railroad was something they may only read about in history books when units in school discussed the Civil War. The history seemed very far away.

Others also may have learned the story of the runaway slave and abolitionist Harriet Tubman’s exploits in those books, as well as movies and television.

But when further explored, the story takes on an interesting local twist in Oswego County’s cities, town and villages of Oswego, Scriba, Hannibal, Mexico, Fulton, New Haven, Richland, Pulaski, Hastings, Constantia, Schroeppel, Gilbert Hills, Port Ontario, Volney and Granby.

After making her own successful escape to freedom, Tubman became a resident of Auburn and a highly-sought after fugitive.

Known as “Black Moses,” she made 13 additional treks south of the Mason-Dixon Line using a network of antislavery activists and safe houses collectively being known as the Underground Railroad.

Serving as the railroad’s most noted conductor, Tubman and others led their flocks North to freedom preceding the start of the Civil War through northern portals including Oswego County’s nearby cities, towns and villages. Fugitive slaves found safe harbor among many abolitionist citizens before final passage via Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River to Kingston, Ontario, and other parts of southeastern Canada. Others decided to remain in Oswego, Volney, Fulton and other locations near the border of Lake Ontario in Central New York.

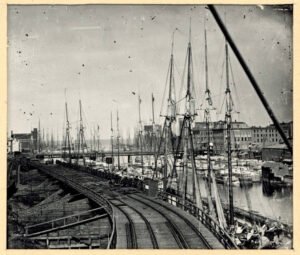

Former SUNY Oswego professor and historian Judith Wellman did prolific research on the topic and noted in a 2010 story in Oswego County Today, “Oswego was an extremely important stop on the Underground Railroad. It was maybe the largest border trade port with Canada in the country at the time.” And Oswego served as a natural port of escape for fugitive slaves looking for freedom.

Because of Oswego’s proximity to Lake Ontario and access to shipping throughout the western Great Lakes and Canada, many homes and antislavery sympathizers in the city secretly provided a stopping point before the next legs of the runaways’ journey to freedom. Often, local farmers, lawyers, business people, homemakers and resettled former slaves were there to provide help.

Upon arrival to Oswego and the area the indigenous Native American Iroquois tribe described as “the small water pouring into that which is large,” numerous houses within the town and city of Oswego, along with their abolitionist occupants, served as important stops. They became the runaway slaves’ final destinations before being led to the “large water” — Lake Ontario — en route to freedom in Canada.

According to the National Register of Historic Places, Oswego County has more Underground Railroad sites than any other county in the country. The runaways, most of the time with only the clothes on their backs, were taken in and offered shelter by people of modest means who believed and lived to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence — “…all men are created equal” and the biblical commandment to “love thy neighbor as yourself.” Often, the freedom seekers would be housed in attics, cellars, kitchens, barns and even wood piles. Men would transport the fugitives from one stop to the next, while women provided food, clothing and care.

Homes along the way included the Starr Clark Tin Shop and Orson Ames House in Mexico, the David Kilburne House in New Haven, the Hiram and Lucy Gilbert House in Schroeppel and the Bristol Hill Church in Volney.

Each served as vital harbors of safe haven for runaway slaves before reaching the Port City.

The Pease House, a Federal-style constructed farmhouse built in the period between 1816-26, on Cemetery Road at Bunker Hill Road in the town of Oswego was owned by Daniel Pease (1793-1847) and his wife, Miriam Rice Pease (1784-1847). Through two generations, the Pease House provided refuge and shelter to runaway slaves and was an important stop during the Auburn-Oswego section of the Underground Railroad.

Tudor E. and Marie Grant (134 W. Bridge St.) also were prominent in the movement.

Tudor Grant, a former slave in Maryland, came to Oswego in 1832 and became an outspoken abolitionist, barber and African-American leader. Nathan and Clarissa Green (98 W. Eighth St.) were one of about 15 African-American families in Oswego in the 1850s who also lent their support and guidance to freedom-seeking fugitives. John and Harriet McKenzie (96 W. Eighth St.), born into slavery in South Carolina, owned their house from 1848-57. John McKenzie was a cartman and heavily involved in Underground Railroad work. White abolitionist Abram Buckhout owned the still-standing Buckhout-Jones Building on the northeast corner of West First and Bridge streets, in which African-American barbers Charles Smith and Tudor Grant operated a barbershop in the basement, which also served as a guiding post for information. And, Gerritt Smith, who owned and later donated the structure that has served as the city of Oswego’s Public Library — the oldest public library in continuous use in New York state according to the National Register — was also a well-known local activist and abolitionist.

“The Pease House is still around,” town of Oswego historian George DeMass explained. “The original floors are still in the house. Unfortunately, the barn area where the runaway slaves stayed, is not standing. The house remains in the family to this day.”

While it is unverified if Tubman ever made her way to the Port City, DeMass explained that other notable abolitionists of the time did, including Rochester resident Frederick Douglass.

“Locally, in the town of Oswego, there is Daniel Pease in Fruit Valley,” DeMass explained. “Alvah Walker, Dr. Mary Walker’s father, was also a great abolitionist.”

Of course, most Oswego residents are familiar with Dr. Mary Walker as the first woman to ever receive the Congressional Medal of Honor for her work as a doctor during the Civil War. Walker also is recognized for her early efforts in breaking racial and gender barriers that she witnessed as the daughter of one of the area’s leading abolitionists.

Often, these days, when Central New York is mentioned in historical terms it is associated with the levels and amounts of snow accumulated during a storm or winter season. The story of Oswego County’s “trail to freedom” is less told and almost forgotten except for the important work of local historians and educators.

“It’s important because freedom is so precious,” DeMass stressed. “Even today, we’re realizing the slavery of people in the past, as well as today. It’s important to keep these stories alive so that people don’t forget [the lessons]. So much happened between Central and Western New York concerning the abolitionist and anti-slavery movements, as well as women’s suffrage.”

For more information about the role played by Oswego Country residents in the Underground Railroad visit any of the following locations: Oswego County Historian’s Office, Oswego County Historical Society, H. Lee White Marine Museum, Penfield Library at SUNY Oswego, Oswego Public Library, Fulton Public Library, Pulaski Public Library and the Ainsworth Memorial Library in Sandy Creek.

Did You Know?

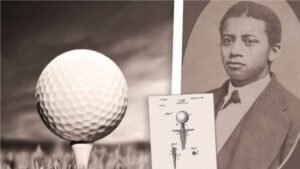

Oswego Native Credited With Inventing the Golf Tee

Dr. George Franklin Grant, born in Oswego in 1846 to runaway slaves from Maryland, Tudor Grant and Phillis Pitt Grant, is a part of golf history.

Having settled in Oswego, Grant’s parents became staunch abolitionists that helped provide safe passage to other runaway slaves through the Underground Railroad in Oswego.

George later went on to attend Harvard University and finished his studies as the school’s second African American graduate of the dental school. He also became Harvard’s first African American faculty member.

While Grant was a gifted dentist and inventor of a patented prosthetic device he called the oblate palate, worn by patients to help their palates move into proper physical alignment and allow them to speak and eat more normally, it may be his love for the game of golf that has led to his most lasting legacy.

As one of the earliest known African American golfers in the post-Civil War era, one area of the game that frustrated him while playing in the Boston suburb of Arlington Heights was the imprecise, messy and unsanitary process of teeing up the ball by pinching clumps of moist sand to construct a cone-shaped tee. In search of a better method, Grant devised an invention that remedied his frustration.

When U.S. patent No. 638,920 was granted to the passionate dentist and golfer on December 12, 1899, the sport of golf would be forever changed. Described as a “rigid base portion and an attached flexible head, with the base preferably made of wood and tapering to a point at its lower end to be readily inserted in the ground,” Grant’s golf tee invention also featured a gutta-purcha crown — a latex resin used in dentistry – in which the ball would sit.

An inventor with little business savvy, Grant never marketed his golfing innovation, instead choosing to pass out the Arlington, Massachusetts-manufactured tees by the handfuls to his golfing buddies. More than 80 years after his death in 1910 at the age of 64, the Oswego-born native, pioneer, inventor, dentist and golfer was recognized in 1991 by the United States Golf Association for his contribution to the game.

Tom and Jerry Caraccioli are freelance writers originally from Oswego, who have co-authored three books: “STRIKING SILVER: The Untold Story of America’s Forgotten Hockey Team,” “BOYCOTT: Stolen Dreams of the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games” and “Ice Breakers.”

Tom and Jerry Caraccioli are freelance writers originally from Oswego, who have co-authored three books: “STRIKING SILVER: The Untold Story of America’s Forgotten Hockey Team,” “BOYCOTT: Stolen Dreams of the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games” and “Ice Breakers.”